In the essay, 'A Review of Three Recent Dictionaries of Indigenous Languages Spoken in South America,' authors Dr. Mark Turin, Associate Professor of Anthropology at UBC, and Ana Laura Arrieta-Zamudio, PhD Student in Linguistics at UBC, compare three recent dictionaries of Indigenous languages spoken in South America. The review covers two print dictionaries—one of which is trilingual (Quechua, Spanish and English) and the other the second edition of a bilingual Q’eqchi’-English dictionary—and a bilingual, digital dictionary hosted online (Wichí-Spanish).

In this Q&A with Language Sciences, Ana Laura Arrieta-Zamudio explains how analyzing dictionaries can give insight into the history of language, how language production and reception are central aspects of making a dictionary, the importance of OPAC principles, and more!

1. What are some ways that analyzing dictionaries can give us insight into the history of a language and culture?

In my opinion, analyzing dictionaries can provide us with valuable information about the history of a language and its associated culture. Many dictionaries include a brief section on the language's history and the region where it is spoken, as well as a section devoted to discussing various related cultural aspects. Additionally, dictionaries can offer insights into the cultural differences that exist among the different dialects spoken in various regions, whether or not the dictionary explicitly documents them. It is fascinating to examine the decisions made regarding whether or not to include internal dialectal variation in the dictionary under consideration.

2. Why do decisions regarding dictionary entries take on greater relevance in Indigenous language lexicography? What are some variables that are considered?

The entries in an indigenous language dictionary are incredibly important for lexicography. In the case of English or Spanish dictionaries, major academies make decisions about what to include, resulting in prescriptive rules. However, when compiling a dictionary of an Indigenous language, there is no academy to make these choices, and they must rely on the compiler and members of the language community. These choices can have a significant impact on the communities where the language is spoken, and they may involve different areas such as politics, culture, and society. Variables that must be considered include the orthography used, the lexical order to follow (whether it should be based on the language's own orthography or not), whether the dictionary contains words currently in use in the community, and if it includes additional grammatical information (like a description about nominal and verbal information of the language, etc.), loanwords (either from English or Spanish), or neologisms.

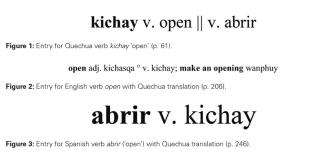

Here I show you an entry of the Quechua-Spanish-English Dictionary: A Hippocrene Trilingual Reference:

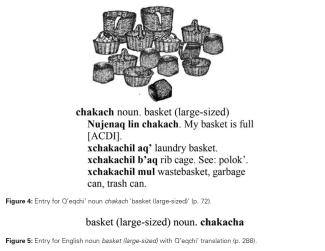

Here is an entry of the Q'eqchi' Mayan Dictionary: Second Edition

And an entry of the online dictionary [Diwica] Wichi-Siwele Lhayhilh/ Diccionario Castellano-Wichi:

![An entry of the online dictionary [Diwica] Wichi-Siwele Lhayhilh/ Diccionario Castellano-Wichí:](/sites/default/files/styles/max_325x325/public/2023-05/picture3.jpg?itok=5cQF5JJs)

3. What does it mean for Quechua to be an agglutinative language, and what challenges are faced when conducting dictionary translations of agglutinative languages?

Agglutinative languages use a large number of morphemes to convey multiple meanings in a single word, which can make creating a dictionary challenging. The Quechua-Spanish-English Dictionary: A Hippocrene Trilingual Reference was compiled by Odi Gonzales, Christine Mladic Janney and Emily Fjaellen Thompson in 2018. This dictionary focuses on the variant of Quechua spoken in the Cusco region of Peru, also known as the Cusco-Collao variety and a form of Southern Peruvian Quechua; although, the dictionary was published in the United States.

Since English and Spanish are not agglutinative languages, it is challenging to convey the meaning of words from agglutinative languages like Quechua into these languages. Sometimes, a single word in Quechua can convey a full sentence, like the word "wanphuy," which can be translated into the English sentence "make an opening."

As a trilingual dictionary, the process of translation posed additional challenges. In some instances, the authors note that certain Quechua words have a more direct translation into either English or Spanish, but not both. In other cases, the compilers chose to include both a literal and a free translation to ensure clarity and accuracy.

4. Can you expand on how language production and language reception central aspects of making a dictionary?

Language production (speaking and writing) and language reception (reading, listening, and comprehension) are fundamental aspects in creating a dictionary. In Indigenous language dictionaries, language revitalization and reclamation are the primary focus. As such, language production takes precedence, and more space is dedicated to representing information about the Indigenous language, particularly its orthography and pronunciation. Since many Indigenous languages have a limited history of written tradition, these dictionaries play a vital role in promoting language reception in the long term. By encouraging learners to write, read, speak, and listen to other learners, these dictionaries facilitate the language revitalization and reclamation process.

5. What are OCAP principles, and why are they important?

The principles of OCAP (Ownership, Control, Access and Possession) within First Nations communities are vital and beneficial for all scholars collaborating on language projects with Indigenous communities. These principles assert that Indigenous communities have control over all data collection processes and should own and control how their information is used, stored, interpreted and shared.

One effective way to incorporate OCAP principles is by acknowledging community participation and recognizing the specific contributions of individuals. In a dictionary, it is crucial to acknowledge community members who contributed to the work and ensure that the community has access and possession of the compilation. The Quechua-Spanish-English Dictionary, for example, includes an acknowledgement section on the first page, where the authors thank the Quechua and Kichwa speakers who contributed to the work. On the other hand, the Q’eqchi’ Mayan Dictionary: Second Edition lacks a self-standing acknowledgement section and does not explicitly reference the efforts of any named native speakers. However, it does offer some general features of the Q’eqchi’ language and the territory in which it is spoken.

In summary, OCAP principles provide an essential framework for scholars working with Indigenous communities to ensure community participation, control, access and possession of their language and cultural knowledge. Acknowledging community participation and contributions in a dictionary is one effective way to showcase and highlight these principles.

To learn more and to read the full essay, click here.

Written by Kelsea Franzke