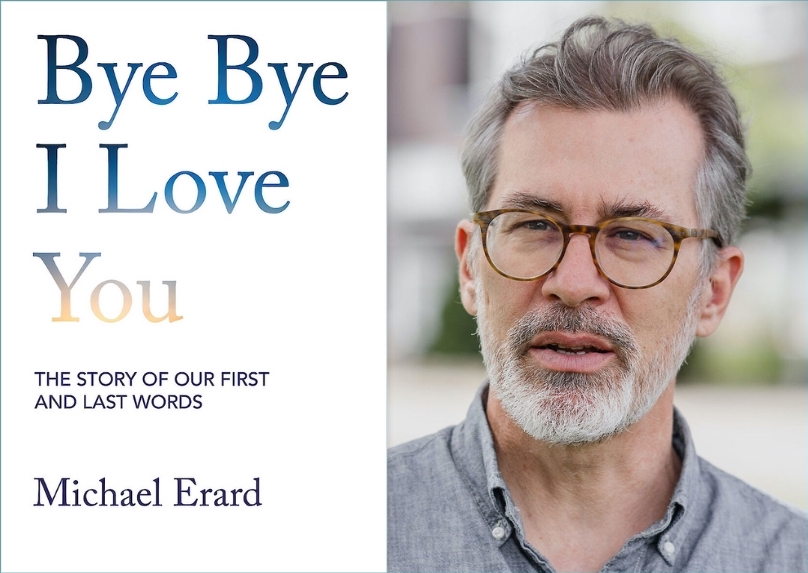

When linguist and author Michael Erard stumbled upon some yellowing bones in the puckerbrush on his berry-picking excursion one day in 2022, it took him a moment to recognize and reconcile with the sight of death. Several weeks later, authorities divulged the identity of the dead person -- a homeless person named Toina Hanson, gone from the street for a year, unnoticed. The unexpected shock prompted Erard to read vigorously about cultural diversity around death and burial while welcoming his second home-birth child, eventually meandering his way into the making of Bye Bye I Love You, an investigation into human's first and last words.

We spoke to Michael about his new book.

Your book Bye Bye I Love You discusses first and last words from a variety of perspectives across disciplines. In a few lines, can you describe your approach?

I sometimes try to give a label to this. One that seems to work is “historical linguistic anthropology.” Basically, the ethnography of speaking asks, “what counts as an utterance, and to whom?” and I interrogate the answer for first and last words historically, but also cross-culturally. Humans are enculturated organisms and embodied selves, so I reach for ideas, concepts, resources and sources to tease apart the social and the organic along the historical dimension.

I’m also irritated by presentism, this idea that things have always been the way they are now. There’s a fixed mindset that results from this. One benefit of seeing culture in a historical way is that you realize things can be changed.

Culture plays a large part in your book. How does culture shape the way we construct and perceive first and last words?

Culture plays a huge part in the book! It shapes how the person is held and constructed, and what the limits of that personhood are. It shapes who is seen as a legitimate conversational or interactional partner. It provides some guard rails for understanding the risks of not following the cultural ideas, whatever they are. And it also sets the expectations about what “firstness,” “lastness,” and even “wordness” are about in the first place.

But lest I make it seem like a unitary “culture” is an all-powerful agent here, I want to acknowledge that very real, material factors (which I write about) come into play–for instance, that public health reforms that reduced infant mortality increased the likelihood that kids would have first words, while medical practices at the end of life can frustrate the ideal death in which there’s meaningful interaction. Parents who do agricultural work may well value face to face time with their babies but can’t afford to. So material factors and cultural forms interact with each other.

3. Contrary to general perception, first and last words are often not "words" per se. Can you explain this further, and why is it important for us to understand this?

Sometimes the clearest intentional articulation of personhood or consciousness appears as a nonverbal, not a spoken or signed word. This makes sense–language is multimodal, after all.

Understanding this is important because many of people’s stories, particularly at end of life, are about gestures and facial expressions that are meaningful to them. And it’s clear that people have to adjust their communication resources as the interaction window changes at the end of life. You can’t map the trajectory of those changes unless you’re aware of what else goes on, including silence.

It also exposes a commitment to words in some societies and traditions that’s almost theological, and as a result non-lexical aspects of language get pushed to the periphery in all sorts of domains. Looking at first and last words makes you treat language more holistically. If you’re going to look for a limit or threshold, then let’s look. In regards to early language, a first point is a good developmental milestone and often clearer than spoken utterances.

It also makes you realize how some fundamentals of the system remain intact across the lifespan, such as turn-taking. So at the end of life, it’s wrong to think that people have been “reduced” in any way, when some very basic properties of the communication system can still function.

4. The book starts with one of your encounters with death. How has the writing journey change/ inspire you on the subject of death since then?

I understand more clearly now what happens in regards to language at the end of life, what will be asked of me at deathbeds I visit and what I may experience at my own. It has impressed on me the importance of knowing the right things to do for the dying and the dead, practicing them, and teaching them.

5. What do you hope readers to take away from the book?

I hope that the book gives people permission to re-narrate their personal stories around these linguistic milestones. I also hope it helps people to see that their cultural models around early language and language at the end of life may not contribute as positively as they think. This is especially the case with language at the end of life, where there seems to be a persistent notion that we retain our linguistic powers all the way to the last breath, which just isn’t the norm. There is also a fantasy that being present at someone’s final moment is somehow required, but in terms of bereavement outcomes, that’s not the case. So I hope the book gives people a simple idea about what language at the end of life is actually like, in the same way they have a basic idea of what babies’ language is like.