When languages fade, so does the world's rich tapestry of cultural diversity.

That’s according to the United Nations, which declared February 21st is International Mother Language Day in 2000 to promote linguistic and cultural diversity and multilingualism.

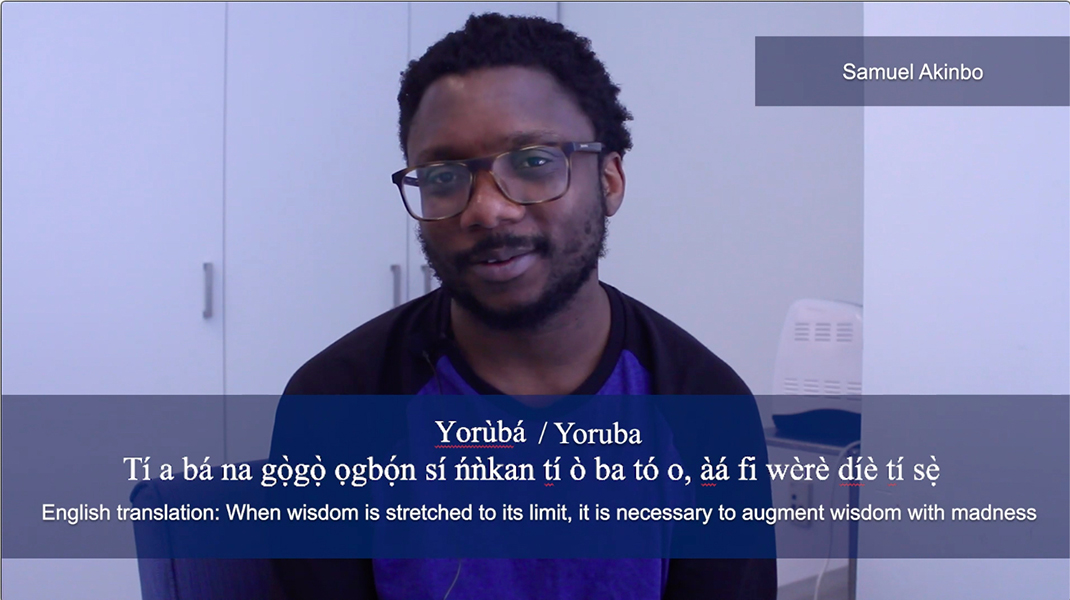

Language Sciences spoke with six bi- and multi-lingual members and colleagues about how their work investigates mother language use, why they think it’s important to speak it, and some of their favourite phrases – click the video below to hear them.

How does your work investigate mother language use?

Dr. Dzéiwsh James Crippen (SFU First Nations Language Program, heritage language speaker of Tlingit): I work on Tlingit, a critically endangered First Nations language spoken in Alaska, BC, and the Yukon. Its syntax is often seen as ‘impenetrable’ by those from a European language background. My aim is to dispel some of these myths – it’s structured, it’s not some alien language, it’s just another human language.

Dr. Stefka Marinova-Todd (School of Audiology and Speech Sciences, Bulgarian): I have been studying bilingualism since I was an undergrad student and currently I teach a Linguistics course in second language acquisition. Most of my research on bilingualism has focussed on what effects the mother language has on learning subsequent languages, which explains a lot about someone’s proficiency in a second language.

Dr. Zoe Lam (Asian Studies, Cantonese): In my research, I ask, what is a mother language, when an individual’s dominant language is different from their parents’, as with heritage language speakers? I’m looking at my mother tongue from a different perspective, as we don’t often look at communities of those speakers residing outside the country of that language.

As a teacher, I can offer Cantonese heritage learners a safe space to practice.

Dr. Sonam Chusang (Asian Studies, Tibetan): I have been teaching Tibetan for the past 15 years. Pema and I realized that, although everyone wants to revitalize the language, there is no set template or material for children to learn from. We worked together on Storybooks Himalaya so that Tibetan parents and children can have such a resource.

Samuel Akinbo (Linguistics, Yorùbá): I work on endangered and understudied languages. I also work on Yorùbá. As a native Yoruba speaker, my insight on the culture and the language guide my research.

Why is it important to speak a mother language?

Pema Choedon (Storybooks Himalayas voice actor, Tibetan):

It’s about identity.

Young kids, if they can say, I’m Tibetan, but they don’t know how to speak Tibetan, they feel uncomfortable. My daughter swaps Tibetan words at school with a friend who speaks Cantonese, she learns a new word every day.

SC: Cultural learnings are part of language. You almost have to shift your mindset when you speak another language. Preserving a mother language is good for Canada too, it brings new cultural values to the country and contributes to the shared discussion.

DJC: There’s a steep decline in the use of heritage language in the third generation after immigration. We often see deep regret in this generation about this, because they feel as though a part of their identity has been taken or denied. And this is in situations where there is no active oppression. In situations with active oppression of the language, even fluent speakers can feel like part of their self is damaged or lost.

Language is an essential part of every human’s identity.

SMT: Maintaining one’s mother language is enriching, both culturally and linguistically. And, my research has shown that exposing children with autism to two languages does not make their lives harder which is contrary to a commonly held belief that parents should speak only the language of the community outside of the home, to make things ‘simple’.

SA: It’s your identity. When Black Panther came out, many African Americans were excited to see themselves represented. It wasn’t a big deal for me, because I don't know what it’s like not to have the language, and the cultural history that comes with it.

ZL: It’s important to have linguistic diversity, because you look at things through a different lens. It would be so boring if we all looked at things the same.