Machines that can learn have long been the stuff of science fiction, and questions about the possibility of killer robots come up often enough that Language Sciences member Mark Schmidt has a slide answering this in one of his presentations.

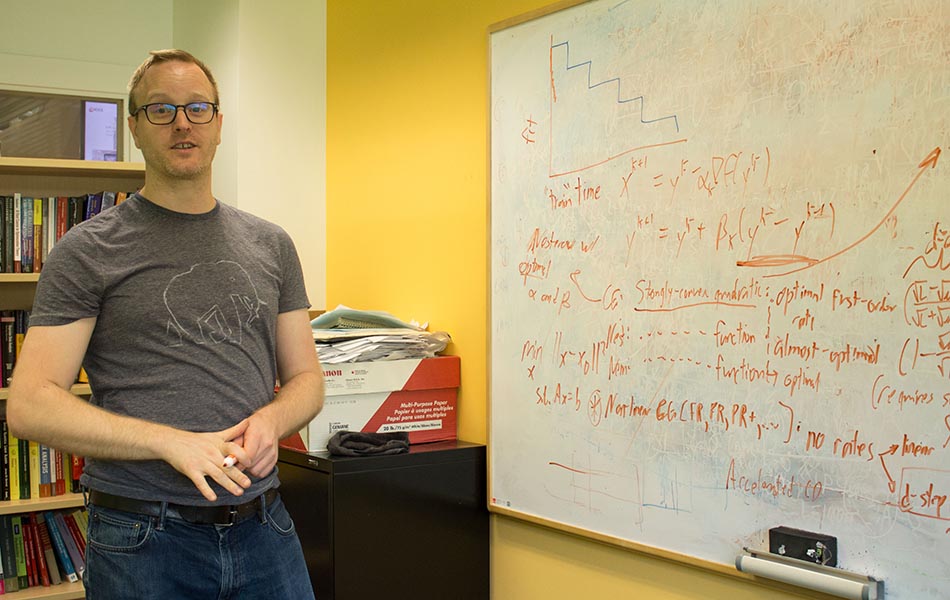

As Canada Research Chair in Large-Scale Machine Learning and University of British Columbia Computer Science associate professor, Schmidt could be expected to know what he is talking about when he says that no, human technology is not close to Skynet, “at all.” Language Sciences sat down with Schmidt in May to ask, if building terminators is not involved, what is machine learning?

“If you’ve been on the Internet, you’ve been exposed to machine learning many times already today.”

Machine learning, said Schmidt, involves teaching machines to analyze large amounts of data in order to find patterns which humans can then use to make predictions or decisions. Give a computer program a lot of inputs and expected outputs (for speech recognition software, the input would be a certain combination of sound waves, and an expected output would be the printed words ‘My name is.’) The program then builds a system that works not only with those provided situations but also with new data (for example, understanding a new phrase such as ‘Hasta la vista, baby.’)

The more data you have, the slower things can be, but the more interesting things you can do, Schmidt said. Enter large scale machine learning, which aims to have computers work with huge data sets, quickly. Schmidt’s research investigates algorithms to achieve this efficiency, and last year, his team won the Lagrange Prize for work in this area.

“So in some sense, to me, all data is data, and language is just like another source of data, another source of problems.”

Machine learning has a broad range of applications, from speech recognition software to biomedical technology, geological modelling to translation software. Schmidt’s applications include using a video game to teach a system to recognize cars and distance from other objects, for use in self-driving vehicles, generic counting tasks, including counting the number of penguins in Antarctica, and basic word-labeling tasks, such as ‘where is the verb in the sentence?’ Schmidt said he is data agnostic, working on generic methods that can be used across many applications.

One of the applications of Dr. Schmidt's work includes using a video game to teach a system to recognize cars and distance from other objects, for use in self-driving vehicles.

Language is part and parcel with computer science, Schmidt said, with the field of natural language processing aiming to build systems that understand language, and can interact with humans using language. “In my completely biased opinion, it’s possibly one of the most important language issues.”

While it is not specifically his field, Schmidt said there are many reasons to create machines that can interact well, or convincingly, with humans. Empathetic machines in care homes could help address any manual labour shortage that comes with an aging population, and even just having a computer that could observe, and then replicate, repetitive tasks would help in everyday life, he said.

“But we could sit here all day and try and think of the neat things you could do if you had a very effective language agent.”

In the future of machine learning, Schmidt does not predict killing machines that look like Arnold Schwarzenegger, but there are concerns about the misuse of the technology, including in automated weaponry, for fraud, and possible privacy violations. On the bright side, he believes real-time vision technology, such as pointing a smartphone at a room and asking it to find your keys, is on its way.

His current research focuses on finding a faster algorithm for deep learning, a subfield of machine learning, and demonstrating practically that it works. In general, the future of the field will see “larger and larger data sets that lead to more and more accurate predictions,” Schmidt said.

So, instead of asking about Skynet, Schmidt would prefer people ask, "Can machine learning help with my problem?"

“It doesn't even necessarily need to be a research problem, machine learning can make life easier in a lot of different ways.”