A hunt for elusive bannock inspired Language Sciences member Dallas Hunt to write Awâsis and the World-Famous Bannock, a children’s book celebrating Cree language revitalization.

On a road trip from Vancouver to Edmonton, Dr. Hunt and a friend attempted to follow spray-painted signs advertising bannock. With each sign, the distance changed in nonsensical ways. “We never made it but I’m sure it was the best in the world.”

Dr. Hunt, an Assistant Professor in English Language and Literatures, wanted to create a book to steep Cree children and adults in the language and provide a few words and phrases to enable conversational nêhiyawêwin, especially for those dispossessed from the language.

“It’s crucial for Indigenous communities that we cultivate our languages because they’re under constant attack through a variety of different ways and throughout history.”

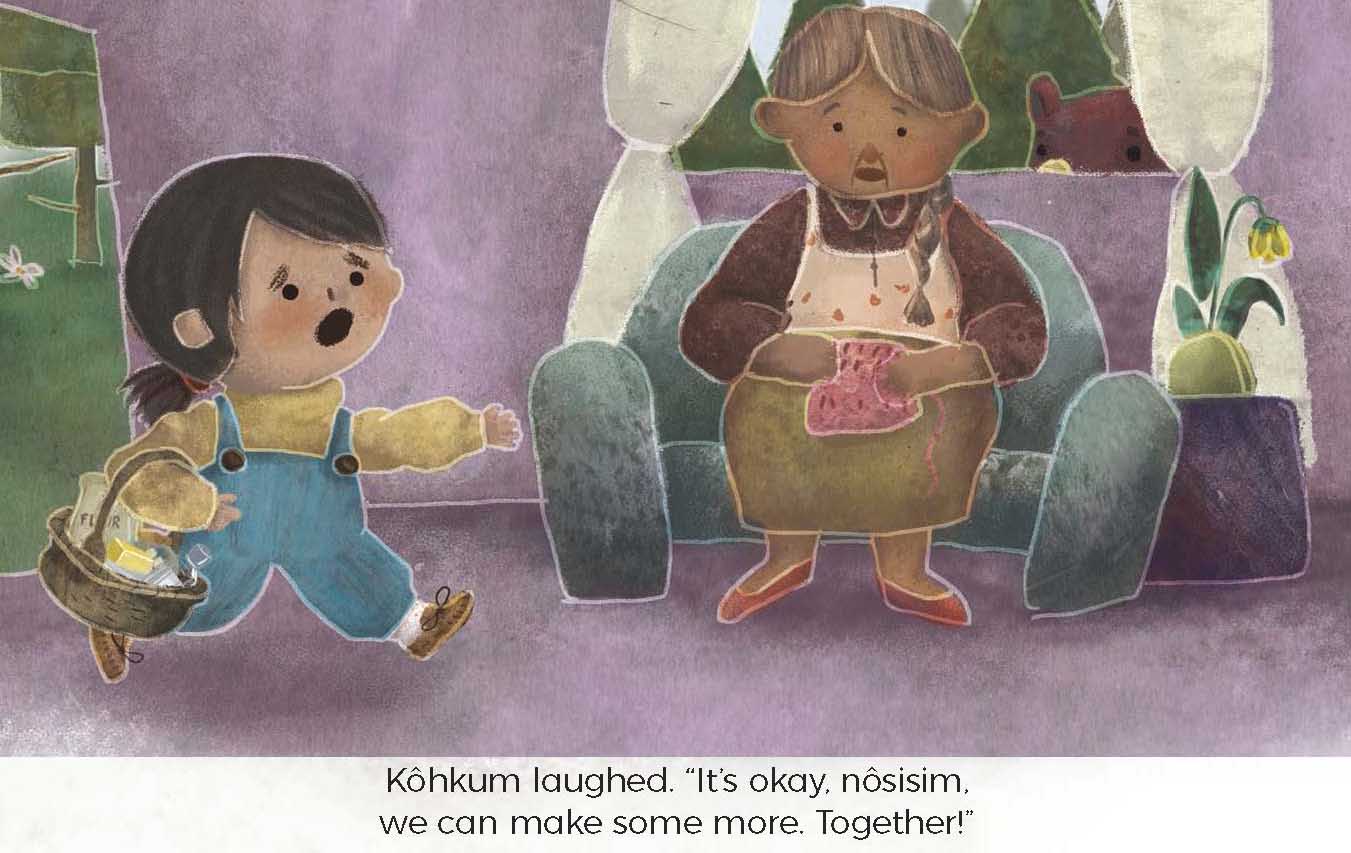

He wrote Awâsis and the World-Famous Bannock in 2018. The book follows the adventures of Awâsis, who loses her kôhkum’s world-famous bannock and receives help from animal relatives in gathering ingredients for a new batch. Peppered throughout are nêhiyawêwin words, and at the back are a pronunciation guide, and a recipe for bannock belonging to Dr. Hunt’s kôhkum.

An adult nêhiyawêwin learner, Dr. Hunt made deliberate choices with regards to language learning that made a children’s book the most suitable genre, including simple language, repetition, and providing illustrations of the nêhiyawêwin words used rather than English translations. The book is not intended as a prescriptive text on nêhiyawêwin, Dr. Hunt says, and there are many different ways to spell all the words used.

“What’s important is having fun and trying to learn the language.”

The book contains a mix of English and nêhiyawêwin, as a wholly nêhiyawêwin text would be inaccessible to many Cree children. Language acquisition is hard to enact because Indigenous communities are inundated with English from birth, and contend with the ongoing effects and structures of colonization, says Dr Hunt. “It’s a process of colonization that it’s hard to learn the languages our ancestors spoke and speak to us.”

“The most encouraging thing for me is that Cree lives on, it’s a living language.”

There is a tendency to consume an Indigenous language without learning about the community’s teachings, Dr. Hunt says, including inherent societal, political, scientific, and legal knowledge. For example, the concept of wahkohtowin, an ongoing process of reciprocity and relationality required to be a good person, is demonstrated in the book by the animals helping Awâsis, including the bear, a potentially frightening character who ends up a friend.

Dr. Hunt toyed with the idea of not including a pronunciation guide, to disrupt the white settler assumption of access to, and extraction of, Indigenous knowledge, but understood the guide could be useful for Indigenous families. “If this [book] cultivates notions of sharing and reciprocity between Indigenous and non-Indigenous folks, that’s not a very bad thing.”

Feedback has been generally positive, he says, with some back and forth about the right recipe for bannock (“my only thought is that raisins don’t belong”) and a refreshing change from sometimes coded academic critique. “I read this to a class of grade two to three students, they are absolutely ruthless with their feedback.”

Kelsa Remy, a kindergarten teacher at Queen Mary Public School, says the book is a classroom favourite. Most of her students have a Cree background and are already familiar with some of the words, such as kôhkum. They use those learned from the book with ease. “If I say ‘sîsîp’, they say, ‘Oh that’s a duck’.” This year, the class made their own bannock using Dr. Hunt’s kôhkum’s recipe.

“These are my students, I would like them to see themselves in the classroom.”

Remy says language revitalization work should start young: “the earlier the better”, including reading books such as Awâsis and the World-Famous Bannock, acknowledging there are languages other than what’s deemed official, and getting students curious enough to learn more. As a non-nêhiyawêwin speaker, a structured program provided at teachers’ training or by the government would be helpful but hearing that Dr. Hunt was an adult nêhiyawêwin learner made it less scary for her, she says. “Adult learners are trying to revitalize the language. If they’re doing that, I can certainly read these books.”

Main image credit: Amanda Strong/HighWater Press. Please note this picture has been edited to fit website parameters.

Picture of children making bannock credit: Kelsa Remy/Queen Mary Public School.