Ever agreed wildly with someone at a party because you couldn’t hear what they were saying? What if a vibrating device could help you understand their speech?

A project headed by Language Sciences members investigated how vibration against skin might help people understand speech in noisy environments. Co-investigator and Cognitive Systems alum David Marino (BA 2016) explains how such a device could be of benefit to workers and hard of hearing populations - and just whether vibrators strapped to our necks is a future possibility.

This project used a vibrating device to try and help listeners understand a speaker in a noisy environment – how might this be useful?

You've undoubtedly found yourself in this situation: you're at a noisy social event, a friend is talking to you, but despite your best efforts, you can only make out half of what they're saying.

You can cup your ears to funnel the sound, but this requires use of your hands. You can circumvent this by taping fun paper cones to your ears, or using a microphone, but augmenting audition alone may not be desirable since there are other sounds you may want to pay attention to.

You could look at the speaker's face, but there are some situations where this is not always possible, such as an industrial shop floor where workers are involved in a collaborative task.

Or, you could use touch. You can place a small vibrotactile device anywhere on the body, freeing up your hands, and relieving you from the need to be facing the speech source.

What is the device, where do you wear it, and how does it work?

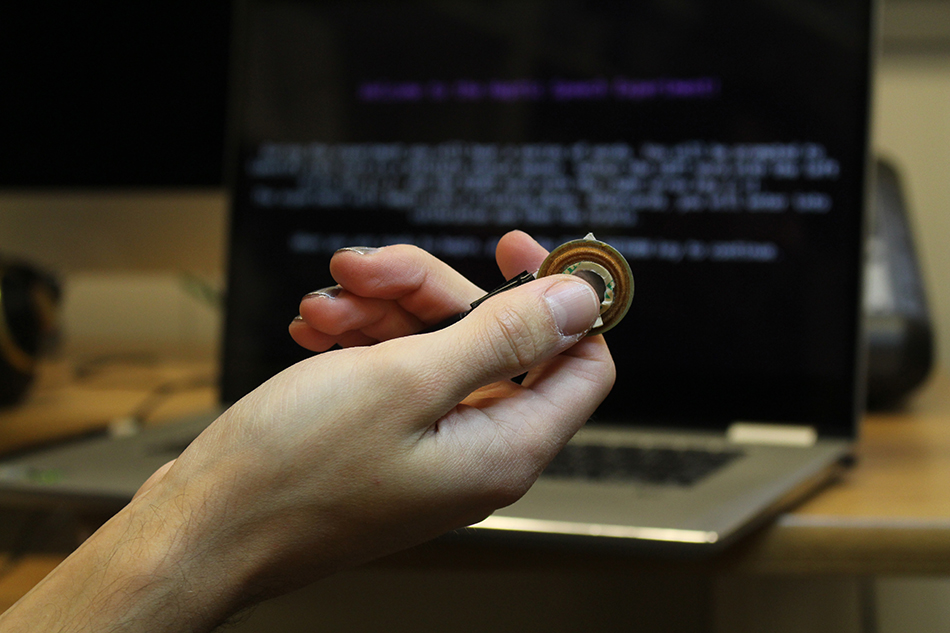

It currently consists of a small loonie-sized vibrator which is hooked up to a computer that translates speech to touch. The system will take a digital audio signal (speech), slice it up, and analyze each increment to determine whether or not the vocal folds are vibrating. If it seems likely that they are, then the vibrator activates, with the intensity corresponding to the loudness of the source.

We explored wearing the device in various locations on your body, such as the fingers, or even in the notch of your throat, right by where your vocal folds are. In an exploratory pilot study it looked like all placements are similar in their efficacy.

Pictured: Co-investigator and Cognitive Systems alum David Marino wearing the device on the throat.

What are some of the potential practical applications?

Consider workers in an auto shop. It's an environment where they cannot maintain eye contact while working, and where ambient noise is critical to safely operating the equipment. Using the tactile modality to enhance speech is thus ideal here.

This could also be of use for hard of hearing populations. While there has been a fair amount of research looking at using multi-channel (multiple vibrator) vibrotactile devices to enhance speech, there haven’t been many evaluations of single-channel (only one vibrator) devices. This is an interesting area because many people already own a single-channel vibrator, such as a phone or smartwatch.

So if proven effective, this system could easily be implemented in these everyday objects. I should note that most of the evaluations we have done with this system so far have been in a non-clinical population, and that affects its design.

What did the project find?

We ran an initial study, published in Canadian Acoustics in February, and found that there is a 9% enhancement in intelligibility when wearing the vibrator. While the enhancement is statistically significant, we were curious as to how useful such a boost in intelligibility would be in everyday situations. Future work could evaluate this, as well as look at some other methods to further bolster the enhancement.

We also found that latency between hearing the speech and feeling the vibrations didn't matter so much--so this bodes well if implemented in a realtime system.

Can we expect vibrating neck devices in the near future?

I don't expect us to be strapping our cellphones to our necks any time soon. There's still a few core usability problems and basic research questions we need to figure out.

The project is exciting in its very diverse range of application areas, and just the idea that feeling someone's voice through your skin helps you hear them better is super cool!

This project received funding from the Language Sciences Initiative and involved Language Sciences members Computer Science professor and Principal Investigator Karon MacLean, and Language Sciences co-director and Linguistics professor Bryan Gick.